We read a lot about cloning in the news these days. Ever since Scottish scientists created "Dolly," the first cloned sheep, in 1997, there has been lively debate about cloning and the possibilities it raises.

There are several types of cloning, although we tend to think primarily of cloning in the reproductive, or Dolly sense of the word. In Dolly's case, scientists removed the nucleus of an egg cell taken from one sheep, and injected a mammary gland cell from another sheep into the nucleus-free egg cell. This specialized cell, which in time became Dolly, was implanted in the uterus of a third sheep, who served as Dolly's surrogate mother.

In addition to reproductive cloning, molecular biologists have been cloning genes and DNA since the 1970s for laboratory work. And therapeutic cloning (sometimes called embryo cloning) research is under way, with the goal of harvesting stem cells that can be used to treat disease and for other purposes.

Therapeutic cloning has drawn a great deal of criticism and generated ethical concerns because it requires the use of human embryos.

There are plenty of books and websites from which you can learn more about all types of cloning. If you're interested, it would be a good idea to learn what you can, as cloning promises to continue to be a hot topic in our society.

For the purposes of this experiment, however, you needn't get excited about stem cells or DNA or anything like that. The experiment in this section deals with plant cloning, which is simply making a plant that's identical to another.

So What Seems to Be the Problem?

The problem you'll attempt to solve during the course of this science fair project is whether a plant you clone from another plant is better than the original. Let's explain what that means.

In horticultural terms, the word "clone" is used to designate all the descendants of a single plant, produced by vegetative methods. This means that the plants multiply by means other than seeds.

All of the plants that are produced from one plant have a common origin, and are considered extensions of a single plant.

Cloning of plants, or artificial plant propagation, commonly involves separating a portion of the parent plant in order to produce an independent plant. Almost any part of the plant, including roots, stems, and leaves, is capable of vegetative reproduction.

The cloning of a plant can be accomplished in several ways, including the following:

- Leaf cuttings. Removing a leaf from the original plant and planting the stem of it in soil can eventually produce a new plant. This occurs with common plants such as African violets, snake plants, gloxinia, and several species of begonias.

- Certain plant leaves, when cut from their stems and placed flat on top of the soil, develop roots at particular intervals along the cut veins of the leaf. Eventually, the parent leaf looks as if it has sprouted several baby plants, all growing vertically from the leaf at various points along the veins. Plants that reproduce in this manner include begonia and geranium.

- Stem cuttings. Removing a piece of a stem from a plant and inserting it in soil either horizontally or vertically is another method of cloning. Eventually, roots will develop downward from the stem, and a new plant will emerge from the top. When a bud is emerging from a stem and the stem is cut from the plant, a new plant will develop from the bud. Plants capable of this sort of reproduction include begonia, gardenia, Christmas cactus, lantana, and impatiens.

- Budding. This method of cloning is common in the propagation of many fruit trees. A bud, which is an undeveloped branch, leaf or flower protruding from the stem of the plant, is cut from the parent, placed into a notch made into the parent stem, wrapped in place and allowed to grow until it can be removed from the parent and allowed to grow in soil on its own.

- Plant division. Many flowers, such as the commonly found daylily, African violets, certain orchids, and ferns, are cultivated through the division of their thick roots. Once divided, each part can be potted and grown as a new plant.

- Runners. Wild strawberry plants are among those that put out horizontal stems that touch the soil. These stems can eventually develop roots from which another strawberry plant will grow. The new plant is identical to the parent.

- Grafting. A cutting from a plant is attached to a piece of the root, or to the rooted stem of another plant. The two pieces become united, and will grow as one plant. In this method, desirable properties of one plant can be mated with the desirable properties of another to produce a new hybrid plant without producing hybrid seeds. Producing dwarf fruit and oriental trees for home landscaping is a common use of the grafting method.

So as you now know, there are numerous ways to clone plants. Our question is whether the cloned plant is stronger than the original. Does it live longer? Grow better? Resist disease better?

If you want to, you can use the name of this section, "Can Cloning Make a Better Plant?" as the title of your science fair project. Or, you might want to consider one of the titles listed below.

- How Does Cloning Affect the Quality of a Plant?

- To Clone or Not to Clone

If none of those titles strike your fancy, go ahead and make up one of your own. Let's get started.

What's the Point?

Cloning allows for the possible propagation of large numbers of plants with desirable traits, such as a high fruit yield or resistance to disease. When plants are propagated, it means that they're produced in large numbers in order to create a supply of them.

In the world of fruit and vegetable farming, having high-producing plants and trees is advantageous, and often necessary for economic survival. A farmer who can get 50 tomatoes from one plant will be better off than one who's only getting 30 tomatoes.

Most plants employ a method called self-fertilization in order to reproduce. Seeds are produced during this self-fertilization process. Those seeds then fall to -the ground, or are spread by wind or birds or other means.

Some plants cross-fertilize-or cross-pollinate-to produce their seeds.

Insects often carry the pollen, which are the male eggs, from the flower of one plant to the carpal, which is the female receptacle, of a flower of another plant. Seeds form as a result. The plants that grow from these seeds are a cross between the two different plants.

If you want an exact copy of a plant, however, without waiting for self-pollination to occur, then cloning is the way to go.

In the experiment outlined later in this section, you'll use a method of vegetative reproduction (stem cuttings) to clone plants from a parent plant. Your control will be the parent plant, and the cloned plants will be your variables.

What Do You Think Will Happen?

Stem cuttings are a common, and fairly easy, method of achieving vegetative reproduction. You will need a begonia plant, which is a very common plant variety. If you can't find a begonia, you can try the experiment using another type of plant. A begonia, however, should not be difficult to locate.

After you've taken cuttings from the parent plant and grown them into separate plants, you'll want to compare the parent plant with the results of the vegetative reproduction you've achieved. You'll want to see which of the plants appear stronger, have brighter flowers and foliage, produce more flowers, and so forth.

Take a moment here to make a guess about how the plants will compare. Do you think the older plant will be healthier because it's more established? Or that the newly rooted plants will be because of their new growth? Perhaps taking root cuttings from the parent plant will stress the plant to the point that it will become unhealthy.

Go ahead and venture a hypothesis about how you think the cloned plants will compare to the parent plant, and then you'll learn how to take a root cutting and what to do with it once you've taken it.

Materials You'll Need for This Project

You will need, as stated earlier, a good-sized begonia plant, from which you'll take five stem cuttings. It's best to use a sharp, serrated knife (like a steak knife), to cut a stem from a plant. Scissors or a nonserrated knife tend to crush the plant tissue.

To take a stem cutting, make a diagonal cut on a main stem or a side stem. The stem pieces you cut should be about two to three inches long, and contain two leaves at two different points along the cut stem.

To better ensure that roots will form, you can dip the stem into a rooting enhancer such as Roottone or Hormonex. These products contain a chemical that helps generate roots. Using such a product for this experiment is recommended, but not necessary.

Materials you'll need for this experiment are listed below.

- One begonia plant

- Sharp, serrated edge kitchen knife

- Rooting enhancer (preferred, but not necessary)

- Small bag of potting soil

- A plastic, shoebox-size container in which to initially grow the stems

- Plastic wrap or a piece of glass to cover the containers

- Plastic pots in which to transplant the growing plants later in the experiment

- Metric ruler

Once you understand how to make root cuttings and have assembled the necessary materials, you're ready to begin the experiment, as outlined next.

Conducting Your Experiment

Be sure to have everything you need ready to go before you begin the experiment. The stem cuttings should be planted into the soil soon after they're made.

Follow these steps:

- Pour the potting soil into the container in which you'll be planting the stem cuttings.

- Make five stem cuttings from your begonia plant, cutting diagonally along the stem.

- Dip the cut ends of the stems into the root enhancer, if using it.

- Place the stem either vertically or horizontally in the soil. If planting the stem upright into the soil, insert about one-third of the stem into the soil. If you lay the stem in the soil horizontally, bury the stem to a depth equal to twice its width.

- Moisten the soil by misting it with water from a spray bottle.

- Cover the container with either plastic wrap or a piece of glass.

- Place the container in a warm, bright area but not in direct sunlight.

- Mist the soil every other day.

- Check the stem cuttings at regular intervals (weekly would be ideal), recording any changes you notice as the stems begin to grow within the container. Be sure to measure and record the height of the plant, and to note other changes and characteristics that you observe.

- Once the stems are established and growing, transplant them into individual pots. Continue to observe the new plants-and the parent plant-over a period of two or three months, keeping close track of what you see.

Keeping Track of Your Experiment

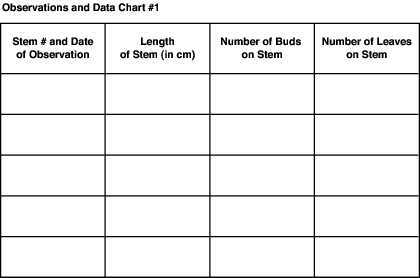

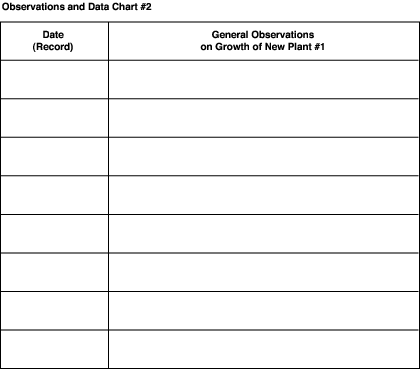

Use the following charts, or make your own charts, to record growth rate and other observations about the five stem cuttings and the parent plant.

Notice which plants appear healthiest, have the most blooms, and so forth. Be sure that all the plants are kept under the same conditions (amount of light and water, and so forth) until your experiment is complete.

Putting It All Together

When you've completed the experiment and have had enough time to observe growth and changes in both the root cutting plants and the parent plant, consider what you've seen.

Do the new plants appear healthy? Are the leaves and foliage of the new plants the same colors as the parent plant? How do the new plants compare in size to the parent plant?

So what have you learned? Does cloning make a better plant or simply an identical plant?

Further Investigation

Many plants that can be propagated through stem cuttings can be rooted in water instead of soil. This method does not require creating the additional humidity, as you did when you rooted cuttings in dirt.

If you're interested in taking the experiment you completed a step or two further, you could root some cuttings in water, and then compare the growth rates and success rates of the two methods.

Begonias can also be propagated by removing a leaf, cutting the veins of the leaf, and placing the leaf on -top of warm soil in a humid environment. Place small stones on top of the leaf to make it lie flat. New plants will grow at the places where the veins were cut.